Counsel from jurisdictions where payments to employee-inventors only arise from contracts or employee incentive programs are sometimes surprised when they first become involved with jurisdictions that have statutory payment schemes for employee-inventors. Intellectual property (IP) management policies not written and designed with these jurisdictions in mind can lead to issues that may come to light only when a problem arises or in diligence. Even if a company has a process in place for making inventor payments, they also, in some circumstances, need to provide locally required notice and information to the inventor. Attorneys outside these jurisdictions need to be aware of these rules when conducting IP diligence, and when they are involved in managing patent prosecution dockets where the priority case originates in jurisdictions that have these requirements. One example of such a notice requirement is in France.

(more…)French IP Law Update – The Delicate Balance between Employers and Inventors: A French Revolution?

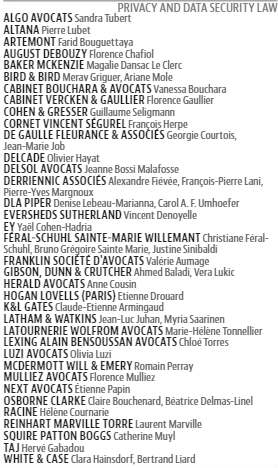

January 20th, 2022 | Posted by in France | Intellectual Property | Patent - (0 Comments)Best Lawyers France 2021 – Privacy and Data Security Law

November 2nd, 2021 | Posted by in France | Privacy | Rankings - (0 Comments)Claude-Etienne Armingaud from K&L Gates ranked among the Best Lawyers France 2021 for Privacy and Data Security Law

Source: Best Lawyers

GDPR – France Fines Monsanto EUR 400,000 in relation with lobbying practices

July 30th, 2021 | Posted by in Competition | France | Privacy - (0 Comments)The French data protection Supervisory Authority (The CNIL) has issued a fine totaling EUR 400,000 against Monsanto for failing to inform individuals whose personal data was collected and processed for lobbying purposes.

Further to the revelation by several media outlets, in May 2019, that Monsanto kept records on more than 200 political and civil society figures (e.g. journalists, environmental activists, scientists or farmers) likely to influence the debate or public opinion on the renewal of the authorization of glyphosate in Europe, the CNIL received seven complaints from individuals whose personal data was included in those records. The personal data included in those records included professional details (e.g. company name, position, business address, business phone number, mobile phone number, business email address and Twitter account), along with a score of 1 to 5, aiming at evaluating their influence, credibility and support for Monsanto on various topics such as pesticides or genetically modified organisms.

(more…)Sapin II – What Recommendations Should Be Followed From 2021 Onwards

April 12th, 2021 | Posted by in France | Privacy - (0 Comments)The French Law n°2016-1691 of 9 December 2016 relating to transparency, the fight against corruption, and the modernization of economic life, known as the “Sapin II” Act 1)Sapin II entered into force on 10 December 2016 (JORF n°0287 of Dec. 10, 2016) introduced to legal entities additional compliance requirements to address corruption in order for France to meet the highest European and international standards.

Sapin II has established a general principle of prevention and detection of corruption risks under the control of a national anticorruption structure, the French Anti-Corruption Agency (AFA), whose main mission is to help economic and public players in the process.

The AFA noted in its 2019 annual activity report 2)French Anti-Corruption Agencyn Annual Activity Report 2019 (7 July 2020) (in French).that anticorruption measures implemented by economic and public players were still incomplete.

On 12 January 2021, the AFA published new recommendations entered into force on 13 January 2021 (Recommendations, here in French).

The AFA specifies the practical procedures for implementing an anticorruption system structured around three foundational principles, namely:

- Governing body’s commitment;

- Understanding the entity’s exposure to probity risks; and

- Risk management.

References

| ↑1 | Sapin II entered into force on 10 December 2016 (JORF n°0287 of Dec. 10, 2016) |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | French Anti-Corruption Agencyn Annual Activity Report 2019 (7 July 2020) (in French). |

GDPR/Data Scraping – A Clear Limitation by the French Data Protection Authority to Direct Marketing Practices

March 10th, 2021 | Posted by in eCommerce | France | Privacy - (0 Comments)The French Supervisory Authority (CNIL) wrapped up 2020 with a EUR 20,000 fine against NESTOR, a French food preparation and delivery company catering to office employees (see full Decision SAN-2020-018 in French).

The CNIL highlighted various breaches of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and the ePrivacy Directive regarding the processing of prospects and clients’ personal data by the CNIL, most notably:

- The lack of prior consent of the prospects to receiving direct marketing communication by electronic means, thereby violating Article L.34-5 of the French Post and Electronic Communications Code (CPCE);

- The failure to properly inform individuals (Article 12 and 13 GDPR) whether:

- Upon the creation of their account on the company’s platform, or

- Upon indirect collection through external sources;

- The failure to properly address Data Subjects’ Access Requests (DSAR – Article 15 GPDR).

While the fine is rather limited in view of the maximum potential amount of EUR 20 million or four percent of the turnover (whichever the greater), this decision presents an opportunity to examine web scraping and direct marketing practices, which are rapidly developing.

(more…)Leaders League Ranking 2020 – Health, pharma & biotechnology – E-Health – France

October 2nd, 2020 | Posted by in eHealth | France | IT | Privacy | Rankings - (0 Comments)COVID-19: French Supervisory Authority Provides Guidance on Personal Data Processing by Employers Amidst Post-Lockdown Return to Work

June 9th, 2020 | Posted by in France | Privacy - (0 Comments)The current COVID-19 pandemic continues to raise many issues on employee privacy and how employers may balance processing their employees’ data with ensuring safety in the workplace. The French Supervisory Authority (CNIL) has provided guidance on the methods that may be used by employers to collect and process health data from their employees (outside of medical care data) in order to detect possible symptoms related to COVID-19, as well as data relating to travel or events. In addition, more generally, the French Labor Ministry has published a “National protocol regarding the end of the lockdown for companies to ensure health and safety of the employees” (Protocol), in order to help employers manage the various tasks and issues related to the end of the lockdown and employees’ return to work. This document does not have legal force, but sets out the general recommendations and principles of prevention regarding the protection of employees’ health and safety in the context of the current health crisis.

Under the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) framework, the CNIL guidance available here in French) reiterates a number of core principles:

Respective Obligations to Ensure and Maintain Health and Safety in the Workplace

Obligations Incumbent On Employers

In the private sector, Articles L. 4121-1 and R. 4422-1 of the French Labor Code (FLC) provide for a safety obligation incumbent on employers, which must implement occupational risk prevention, information and training actions. The company and its legal representatives are criminally liable for the employee security obligation. Employers that fail to provide employees with safe and appropriate working conditions would face a court risk and could be held liable for not ensuring the employees’ safety and security on the workplace. Since 2015, the French Supreme Court has held that the employer’s obligation with regard to employees’ health and safety is an enhanced best efforts obligation (obligation de moyen renforcée). Therefore, the employer can avoid liability by proving that preventive measures have been implemented. French Supreme Court case law holds that the employer has complied with this legal obligation to take the necessary measures to ensure the safety and protect physical and mental health of employee when it is demonstrated that he has taken all measures to prevent, adapt and provide information on the risks, in accordance with Articles L. 4121-1 and L. 4121-2 of the FLC.

In the context of the current pandemic, the employer’s safety obligation is more topical than ever. In order to comply with this mission, employers have the right to process personal data, albeit only when strictly necessary to foster that purpose. In this respect, the CNIL encourages employers to regularly consult the information and recommendations published by the French Labor Ministry, in order to better understand their obligations in this period of health crisis.

According to the CNIL’s position, employers are entitled, in this context, to:

- Remind their employees, when working in contact with other individuals, of their obligation to report to their employers or the competent health authorities in the event of actual or suspected contamination, for the sole purpose of enabling working conditions to be adapted in consequence;

- Facilitate the transmission of this feedback by setting up, if necessary, dedicated and secure channels; and

- Promote remote working methods and encourage the use of occupational medicine.

Obligations Incumbent On Employees

On the other hand, Article L.4122-1 FLC provides that each employee has a safety obligation which requires them to preserve not only their own health and safety, but also, the health and safety of other individuals with whom they may come into contact in the course of their professional activity, be it other workers or customers. However, in practice, employers might be in a delicate situation if they were to take disciplinary sanctions against these employees, and they might face labor court actions.

While French employees are usually only required to provide an illness certificate, which does not provide any specifics on the health status other than inability to work, the CNIL understands that the contagiousness of the COVID-19 pandemic mandates self-reporting be more specific to enable employers to take any measure required to ensure the safety in the workplace.

However, this reinforced duty to provide information does not extend to individuals working in isolated conditions, e.g. without contact with other individuals and/or working remotely. For such “isolated” workers, the classic rules of labor law apply and employers are not allowed to mandate such disclosure of personal data.

The Processing of COVID-19 related Personal Data by Employers

When organizing the return to work, employers are encouraged to facilitate dialogue with its employees and employee representative. Employers may require certain information, and may ask employees to inform the company’s management of, in particular, any travel to risk areas and risk factors related to their health or relatives. However, this organizational requirement must be compliant with the GDPR for the processing of employees’ personal data.

In any case, employers may only process elements related to (i) the date, (ii) the identity of the person, (iii) the contamination status reported by the employee, and (iv) the data related to the organizational measures to be put in place.

The CNIL emphasizes the particular sensitivity of health-related data, which is considered a “special category of personal data” under Article 9 GDPR, and thus requires processing under robust conditions of security and confidentiality, as well as limited access to authorized personnel. Consequently, employers wishing to take steps to ensure the health of their employees must rely on their occupational health service.

Processing operations pertaining to such special category of personal data is, by principle, prohibited under GDPR, unless they fall within one of the exceptions provided under GDPR, namely:

- Consent of the individuals, which is always a difficult basis when processing employees’ personal data;

- Necessity to carry out the obligations in the field of employment and social security and social protection law in so far as it is authorized by Union or Member State law;

- Necessity to protect the vital interests of individuals when physically or legally incapable of giving consent;

- Legitimate activities of nongovernmental organizations and other associations;

- Processing relating to personal data that is manifestly made public by the individuals;

- Necessity in the context of legal claims;

- Necessity in the context of substantial public interest;

- Necessity for the purposes of preventive or occupational medicine, for the assessment of the working capacity of employees, medical diagnosis, the provision of health or social care, or treatment or the management of health or social care systems and services;

- Necessity for reasons of public interest in the area of public health, such as protecting against serious cross-border threats to health or ensuring high standards of quality and safety of health care and of medicinal products or medical devices; or

- Necessity for archiving purposes in the public interest or scientific or historical research or statistical purposes.

In the context of the pandemic, the CNIL highlights that (2) and (8) would be the only relevant bases to ensure the safety in the workplace.

In that regard, the coordination with health authorities, as potential recipients of the data, is authorized, to ensure the medical care of the exposed person. Nevertheless, the identity of the individual, effectively or presumably infected, must not, under any circumstances, be communicated to other employees.

Considering that GDPR and its French implementation only apply to automated processing (particularly computer processing) or to non-automated processing where a physical file is materialized, this means that the simple verification of temperatures prior to access to premises would not trigger application of GDPR insofar as no trace of this check is kept and if no other operation is carried out. On the other hand, any automated temperature verification, such as through use of thermal cameras, would be subject to GDPR. Given that other less intrusive methods to achieve a similar purpose exist, they may not pass muster for the data minimization tenet of GDPR.

ACTION POINTS

Based on the CNIL and French Labor Ministry guidance, the following could be considered by employers in order to effectively and efficiently organize their employees’ return to work:

- Transparency: Employers must remain fully transparent with regard to the processing operations implemented and provide the relevant information through dedicated or amended privacy notice;

- Temperature tests: In principle, temperature logs pertaining to personnel, visitors and customers, as well as automated temperature verification (e.g. through thermal cameras) are not authorized. Indeed, the Protocol published by the French Labor Ministry provides that systematic monitoring of employee temperatures is not recommended. However, if the employer is willing to set up temperature controls at the entrance of the company, it is necessary to (i) post an information note for the employees, and (ii) provide employees with sufficient guarantees (i.e., prior information regarding to the maximum temperature allowed in the premises and the consequences of a positive control, compliance with the GDPR, etc.). Such controls of temperatures could be implemented within the framework of a more global policy stating safety measures in order to preserve the employee’s security and safety when returning to work ;

- Screening test: The Protocol considers that screening tests at the entrance to the company’s premises are not authorized (several groups had announced that they would provide screening tests for their employees);

- Access: Only relevant departments within the company may access the health data collected in the context of COVID-19. Notably, for larger companies, only aggregated and deidentified data, which may not allow any identification of the individuals, can be shared more broadly within the organization;

- Continuity plan: Any continuity plans considered by a company must include specific measures aiming at protecting the safety of employees and identify the essential activities and individuals that must be maintained in order to ensure continuity of service, with such continuity plan, or any professional travel authorization, containing only the personal data necessary to achieve this objective; and

- Transfer: Employers may only communicate such data to qualified health authorities upon request. While no direct communication to health professionals is authorized, employers should direct their personnel to engage with these health professional directly. Similarly,

First publication: K&L Gates Hub in collaboration with Christine Artus, Sarah Chihi, Anne Ragu, Clara Schmit